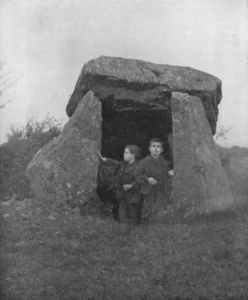

The Loughduff Cromlech, County Cavan

The Cromlech, a photograph of which is given on p. 89, is situated immediately beside Loughduff Church, in the parish of Mullahoran, county Cavan. This is not quite an English mile from Drumhawnagh station, the second station from Cavan, on the Midland Great Western Railway. The cromlech is, as yet, I believe, unrecorded.

The size of the Lough duff cromlech may be estimated with sufficient accuracy by comparing it with the two school-children who stand in the opening. Five uprights support the covering slab. The largest of them may be observed on either side of the door. The covering-stone was manifestly either never placed fairly on top, or else it has been pushed out of its original position. In the case of some of these monuments the covering-stone or dolmen is found with an end or side resting wholly on the ground. According to Du Noyer, the primitive builders, in such instances, with their poor mechanical contrivances, or possibly in the absence of them, failed in their efforts to raise the ponderous table. If this be so, it might be taken as equally probable that this cromlech marks a lesser failure, or greater measure of success. Those who erected it were unable to place it in quite the position they wished.

We are not bound to hold that in the raising of those cap-stones there was one invariable practice. It seems likely enough that in one instance one method was adopted, and in another another, just as circumstances dictated. Small cromlechs would be the first to disappear. I know of one or two ancient stone monuments remaining, which, undoubtedly, are of the dolmen pattern, and which would not need any mechanical agencies for placing them in position. When a greater monument was about to be raised in memory of a greater man, or possibly to commemorate a greater deed, doubtless, when confronted with the problem, the builders solved it on the ground as best they could, and by many devices. As we have seen, they sometimes failed.

On the inside of the upright against which the taller child’s left shoulder is resting there are some artificial carvings or markings. They are of the same general character as those on a living rock near the summit of Ryefield Hill, in the townland of Ballydarragh, county Cavan; but there are not so many, nor are they quite so elaborate. It would be impossible to photograph the inner surface of the stone. The Ballydarragh carved natural rock-surface is minutely described in a paper contributed by Mr. George V. Du Noyer, a gentleman to whom I have already alluded, which will be found in Journal, vol. viii., p. 379. The lithograph illustration which it contains gives a good idea of the carving on this supporter; but that contained in the illustration of another paper by the same antiquary, contributed to Journal, vol. viii. (1866), more nearly resembles it—indeed, it appears almost a replica of it. It faces page 498 of the same volume, and is also lithographed from Du Noyer’s drawing.

These markings, dismissing the supposition that they are mere “weatherings,” are, undoubtedly, of very remote antiquity, but what precisely they mean is another problem awaiting solution. The great and patient labour which was necessary to cut these signs in stone of this nature, without any iron tools, and only by erosion with another stone, “leads us” (writes an expert on this subject) “to the belief that they are not the labour of indolence, and that they have some signification.”[1] A French archæologist, M. Emile Soldi, has attempted to solve the mysteries of such cryptic symbols.

At the cross-roads, about fifty yards in front of the Loughduff cromlech, there was once a good-sized cairn, which no one would pass without throwing a stone on the pile. What was its origin I could not discover. It is unlikely that it had any connexion with the cromlech. In Cavan and Leitrim, the spot where a fatal accident took place used often to be marked by such cairns. In the south of Ireland crosses are sometimes raised. This practice more probably accounts for this cairn; there is no trace of it now. About forty years ago the stones were all carted away as road-metal. It may be remarked that in the same district, about an English mile from the one whose photograph is above given, is to be found another but somewhat smaller one, known as the Middleton cromlech; and in the adjoining parish of Ballintemple, in the townland of Carrickeleven, there is still another. Locally they are called Giants’ Graves or Grania’s Beds.