The Stamp of Government

As we currently negotiate our way through the centenary of the Civil War, various episodes, including the Truce, Treaty negotiations, the fracture of Sinn Féin and the IRA, and the dreadful conflict itself are revisited across the media. However the complexities of the Treaty negotiations and the huge disparity that arose in interpreting its actual terms and potential future benefits still makes the Civil War a difficult and painful subject to fully understand.

One complexity that attended the founding of the Irish Free State was that there were no less than five ‘Governments’ involved at the birth. This confusion of different governments or parliaments, and their often-opposing agendas, can be represented visually with the aid of postage stamps or propaganda labels associated with each one.

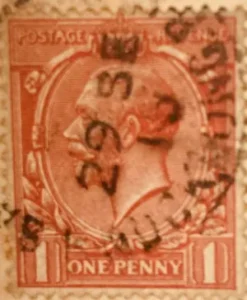

Westminster Parliament 1801-1922

1. The Act of Union came into effect in January 1801 creating a parliamentary union between Ireland and Britain. Thereafter the Westminster Parliament governed Ireland until independence in 1922. British adhesive stamps were first issued in 1840 and were used in their standard form in Ireland until 1922.

The Truce came into effect on 11th July, 1921, when against all the odds, the independence movement forced the British into negotiations. Winston Churchill, a senior member of the British negotiating team, set out their position. The ongoing conflict was seen as bringing ever increasing discredit upon Britain, so compromise was required. He considered that even entering Treaty negotiations with the rebellious Irish was a most questionable and hazardous experiment and that an actual agreement could shake the vast British Empire of hundreds of millions to its foundations. The maintenance of the integrity of the Empire demanded that the granting of republic status to Ireland, an integral part of Great Britain itself, could not be countenanced.

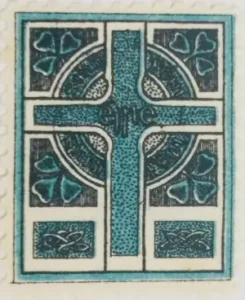

Dail Eireann 1919-1923

2. The first Dail, with 27 Sinn Féin members in attendance, met in Dublin in January 1919 following the December 1918 election in which Sinn Féin won 73 of the 105 Irish seats. Their Declaration of Independence ratified the establishment of an Irish Republic first proclaimed on Easter Monday, 1916. The Dail did not issue postage stamps but since 1908 Sinn Féin issued propaganda labels, with a Celtic cross design, which were occasionally applied to letters or postcards in addition to the required British postage stamp.

Sinn Féin itself was founded in 1905 by Arthur Griffith who initially promoted Ireland’s independence from Great Britain while retaining the British royal family under a dual monarchy system. Sinn Féin underwent reorganisation after the Easter Rising, bringing together Nationalists of different hues, with Eamon de Valera replacing Griffith as President. Its new constitution, to cater for the many shades of opinion, required the party to work for an independent Irish Republic while allowing the people to ultimately choose by Referendum their own form of Government.

As it transpired the actual Treaty Agreement of 6th December 1921 undermined the unity of the Sinn Féin membership. After a bitter Dail debate over a period of three weeks, in which the oath of allegiance to the British throne was central and Partition rarely mentioned, the Treaty Agreement was passed on January 7th. A small majority were prepared to believe that it allowed for advancement to Republic status at a later date. Those opposed, who adhered rigidly to their previous stance, would not countenance anything less than an immediate Republic.

Northern Ireland Government 1921

3. The Government of Ireland Act 1920 established a Northern Ireland Parliament which was formally opened in June 1921. The new Northern state continued to use standard British stamps, at a later date supplemented by Northern Ireland regional stamps.

The Government of Ireland Act 1920 also called for the establishment of a Southern Ireland Parliament but the elected Sinn Féin members instead met in January 1921 and convened the second Dail. The Northern Ireland Government used the period between its inception in June 1921 and the start of the Treaty negotiations in October to establish and entrench its control of the six-county area. It took the unhelpful view that it was not a party to the Treaty negotiations and instead jealously guarded the powers granted to it in the 1920 Government of Ireland Act.

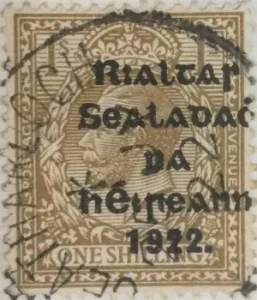

Provisional Government January 1922 to December 1922

4. The Treaty Agreement called for the establishment of a Provisional Government during the interval before the constitution of the Parliament and Government of the new Irish Free State. The Provisional Government of Ireland was installed on 16th January 1922 and shortly after commenced issuing British stamps overprinted ‘Rialtas Sealadach na hEireann 1922.’ (Provisional Government of Ireland 1922.)

Michael Collins was designated Chairman of the new Provisional Government, Arthur Griffith had already been elected as President of the Dail after Eamon de Valera’s resignation. With control of both the Provisional Government and the Dail the pro-Treaty side set about the establishment of a native government system to replace the British administration with the formation of a national army and a new Irish police force to replace the disbanded RIC. By taking over the reins of power, and accepting the handover of British Army barracks, they could demonstrate to the electorate the major gains of the Treaty. At the same time the fracture of the IRA resulted in anti-Treaty forces vying with the Provisional Government to take control of army barracks and other installations from the departing British Army. With two opposing armies, localised flashpoints inevitably arose, it was only a matter of time before full scale conflict broke out.

The general election of 16th June 1922 resulted in the pro-Treaty Sinn Féin candidates and other parties supporting the Treaty winning over 75% of the votes. Buoyed up by the overwhelming endorsement of the Treaty from the people, and under pressure from the British Government, the Provisional Government’s forces finally moved against the anti-Treaty forces occupying the Four Courts in Dublin on June 28th, the Civil War had begun.

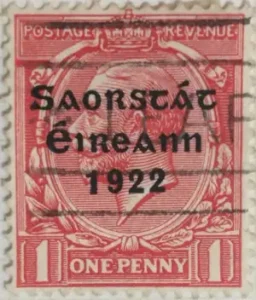

Free State Government December 1922

5. The Free State Government came into being on 6th December 1922, a year after the signing of the Treaty, replacing both the Dail and the Provisional Governments. The newly established Free State Government issued British stamps overprinted ‘Saorstat Eireann 1922’ (Irish Free State 1922). They also began issuing the first definitive series of Irish stamps – including the iconic 2 pence with map of Ireland, shown above.

By the time Free State came into being both Arthur Griffith and Michael Collins were dead. Griffith, who had been in poor health added to by the immense pressures he endured leading the Treaty negotiations and the subsequent turmoil, died on August 12th following a brain haemorrhage. Collins was shot dead just ten days later in an ambush in his native Cork. The Civil War conflict continued after their deaths, mostly confined to the south west of the country, and degenerated into an even more bitter and vicious conflict, with atrocities committed on both sides, and huge damage to the country’s economy and infrastructure. It finally came to an end in May 1923 some weeks after the death of the hitherto unyielding anti-Treaty Chief of Staff, Liam Lynch, following an engagement with the National Army in Co. Waterford.

A Civil War was the worst possible start for the fledgling state. The financial cost and ongoing division were to prove an immense drain and deadweight for decades after its ending. Could it have been avoided? Eamon de Valera originally thought so. He already knew from two months preliminary negotiations with the British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, that the final Treaty outcome was not going to meet with unanimous approval in Ireland. His contentious decision not to partake directly in the later formal negotiations was partly based on that assumption. He would instead remain in Ireland and then promote general acceptance of any Treaty, possibly with some additional minor concessions from the British.

De Valera, apparently wrong footed by the signing of the Treaty and its early publication in the press, quickly departed from his initial plan to be an honest broker. After he failed in his attempt to persuade a majority of his Cabinet not to recommend the Treaty document to the Dail for consideration, he issued a press statement damning the Treaty ahead of the Dail debates. Arguably this action strengthened and gave a lead to the dissension he foresaw would have existed anyway. When de Valera later put forward a slightly amended alternative Treaty, his ‘Document Number Two’, it was dismissed by pro-Treaty and anti-Treaty supporters alike.

De Valera was not an outright hardliner himself, he took only a minor part in the Civil War conflict. Sidelined much of the time by its military leaders, it was only in the closing stages that he managed to regain some control over the political direction of the Republican movement. In 1926, three years after the end of the conflict, De Valera and his supporters broke away from their more hard-line Sinn Féin colleagues to set up Fianna Fail. They polled well in the 1927 General Election and some months later De Valera and his new party signed the controversial oath of allegiance, dismissing it as an irrelevance, and took their seats in Dail Eireann. Following the 1932 General Election Fianna Fail came to power. De Valera and his party would spend the next six years gradually whittling away at the terms of the Treaty, thereby creating a Republic in all but name. In doing so he proved Michael Collins erudite 1921 analysis that while the Treaty Agreement did not provide the ultimate freedom, it gave Ireland the freedom to achieve it. Had Collins’ Treaty opponents trusted his vision, the Civil War and its unfortunate legacy may have been largely avoided.

Notes

All rights reserved by Ken Boyle. Reproduced on Leitrim Books with permission.