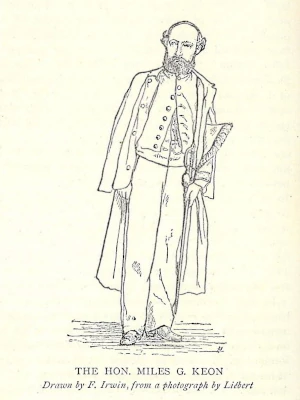

Miles Gerald Keon

Biography

Miles Gerald Keon (20 February 1821 – 3 June 1875) was an Irish Roman Catholic journalist, novelist, colonial secretary, and lecturer. Born into a prominent County Leitrim family, Keon was educated in England and became a cosmopolitan figure whose career spanned both literature and imperial service. He wrote for influential British newspapers and authored historical novels, drawing on his Catholic faith and global experiences in his writings. Under the patronage of notable statesmen, Keon was appointed colonial secretary of Bermuda, where he served for the last sixteen years of his life. He died in Bermuda in 1875 as the last heir of his family line. Remembered in contemporary biographical records, Keon’s legacy endures as a unique blend of literary achievement and public service in the Victorian era.

Early Life and Family Background

Miles Gerald Keon was born on 20 February 1821 at his family’s estate, Keonbrooke, on the banks of the River Shannon in County Leitrim, Ireland. He was the only son of Myles Gerald Keon, a barrister, and Mary Jane Magawly (Countess Magawly’s daughter), and was the last male descendant of the old Catholic gentry family known as the Keons of Keonbrooke. His birthplace was the “paternal castle,” an unusual mansion built of white marble—locally dubbed “Keon’s Folly”. Tragedy struck early in Keon’s life: his father died in 1824 and his mother in 1825, both within his infancy. Miles and his younger sister, Ellen Benedicta, were subsequently raised by their maternal grandmother, the Countess Magawly, and later by their uncle, Count Francis Philip Magawly. (Keon’s maternal uncle had served as prime minister in the court of Marie Louise of Austria in the duchies of Parma, Placentia, and Guastalla, reflecting the family’s broad European connections.)

In March 1832, at age eleven, Keon was enrolled at Stonyhurst College, a Jesuit boarding school in England. He spent eight years at Stonyhurst, distinguishing himself in academics and extracurriculars. Notably, he won a prize for a poem on the accession of Queen Victoria – a piece later reprinted in the school’s magazine during the Queen’s jubilee. Keon’s Jesuit education instilled in him a firm Catholic faith and a disciplined intellectual formation that would influence his later writings. After completing his studies, he embarked on an adventurous grand tour: he made an extensive pedestrian journey across France and ventured into French Algeria, where he briefly served in the French Army under General Thomas Bugeaud. These youthful travels through continental Europe and North Africa provided rich first-hand material that Keon would later draw upon in his journalism and fiction.

On returning to England, Keon initially pursued a legal career. He enrolled as a law student at Gray’s Inn, London, being admitted on 11 November 1840. However, he soon abandoned the law in favor of journalism and literature, finding his true vocation in writing. This decision set Keon on a path that combined his Irish patriotism, Catholic upbringing, and worldly experiences into a distinctive literary career.

Journalism and Literary Career

Keon’s entry into the literary world began in the early 1840s, a turbulent time in Irish politics. In 1843, at the age of 22, he published a political pamphlet titled The Irish Revolution; or, What Can the Repealers Do? And What Shall Be the New Constitution?. Printed in Dublin, this octavo pamphlet addressed the Irish Repeal movement (which sought to repeal the Act of Union with Britain) and proposed ideas for a new constitutional arrangement. The Tablet newspaper noted the publication, indicating Keon’s early engagement with the pressing political debates of his homeland.

In 1845, Keon achieved his first notable literary success – and controversy – with an article in the Oxford and Cambridge Review. Writing in the September 1845 issue (the third number of that short-lived journal), he penned a vigorous vindication of the Jesuits, defending the Jesuit order at a time of prevalent suspicion toward Catholic influence. Appearing in a scholarly review nominally representing both Anglican universities, Keon’s pro-Jesuit piece “provoked a smart controversy,” as one contemporary put it. Its provocative stance generated considerable interest; once Keon’s authorship became known, the article was reissued as a standalone pamphlet. Publishers Longman even announced that Keon was preparing a full History of the Jesuits, although this ambitious book was never completed. The Jesuit article established Keon’s reputation as an eloquent Catholic apologist and showed his willingness to enter the fray of religious controversy.

Drawing on his recent travels in France and Algeria, Keon next turned to writing vivid descriptive pieces for Colburn’s United Service Magazine, a periodical catering to military and naval audiences. Beginning in September 1845, he contributed a series of articles such as “The Late Struggles of Abd-el-Kader, and the Campaign of Isly,” drawing on his personal observations of the French campaign in Algeria. He also wrote installments under the title “An Idler’s Journey on Foot through France,” recounting his long trek across the French countryside. These pieces, which ran through 1846, were noted for their lively firsthand sketches of figures like the Algerian resistance leader Emir Abd-el-Kader and French general Thomas Bugeaud, as well as colorful anecdotes of travel. Keon’s ability to transform his experiences abroad into engaging prose helped broaden his audience and demonstrated his versatility as a writer.

In April 1846, at just 25 years old, Keon was appointed editor of Dolman’s Magazine, a London-based Catholic literary magazine. Although his tenure was brief (April through November 1846), it placed him at the center of English Catholic intellectual life and furthered his editorial credentials. During this same period, Keon made a significant personal step: on 21 November 1846, he married Anne de la Pierre, the third daughter of Major John Henry Hawkes of the 21st Light Dragoons. Anne’s father was an English army officer, reflecting the British milieu in which Keon was now established. The marriage took place in 1846, possibly around the end of his Dolman’s Magazine editorship. There is no record of the couple having children, and Anne would later accompany Keon to Bermuda when he entered colonial service.

By 1847, Miles Keon’s literary output extended to hagiography. He published The Life And Times Of The Roman Patrician Alexis in that year. This work recounted the legends of Saint Alexis, a fifth-century Roman nobleman revered for renouncing wealth to live in poverty. The choice of subject—an ascetic Roman saint—reflected Keon’s devout Catholicism and interest in religious history. With this publication and his previous journalistic endeavors, Keon had positioned himself as a rising Catholic man of letters in London.

Later in 1847, Keon secured a position that would anchor him for the next decade: he joined the staff of the Morning Post (London), a prominent conservative daily newspaper. He became one of the leading writers and remained with the paper for twelve years (circa 1847–1859). In an era when the Morning Post was influential among the British elite, Keon’s role there signified considerable professional standing. He contributed editorials and reports on a range of topics, and his work was esteemed enough that the paper sent him abroad as a special correspondent on major assignments.

In 1850, the Morning Post dispatched Keon to St. Petersburg, Russia, as its foreign correspondent. One of his notable dispatches from this period was A Letter on the Greek Question, dealing with geopolitical and religious issues in the Near East (likely concerning the protection of Orthodox Christians and holy sites — a hot topic in the lead-up to the Crimean War). This demonstrated Keon’s ability to comment on international affairs and ecclesiastical politics. After returning from Russia, Keon continued his language and educational pursuits: between February and August 1851 he authored a series of 26 “Lessons in French” for Cassell’s Working Man’s Friend, a popular educational weekly. These accessible French-language lessons proved quite successful, reportedly finding wide use among readers in the United States and Canada, which hints at Keon’s interest in pedagogy and his international reach even in didactic writing.

Keon’s literary creativity was not confined to journalism and non-fiction. In 1852, he ventured into fiction, writing a novel titled Harding the Money-Spinner. This work was initially released serially in The London Journal in 1852, a periodical known for popular serialized stories. Harding the Money-Spinner is a melodramatic tale centered on a scheming financier, reflecting the Victorian fascination with wealth and morality. Although it gained readers in serial form, it did not appear as a standalone book until many years later: it was posthumously published in three volumes in 1879, a few years after Keon’s death. The delay in book publication suggests that while the story entertained magazine audiences, it might not have been seen as high literature by publishers of the time. Nonetheless, it established Keon as a capable novelist in addition to his journalistic persona.

In 1856, the Morning Post again sent Keon to St. Petersburg, this time to cover a momentous event: the coronation of Tsar Alexander II. Keon’s eye-witness reports on the imperial coronation ceremonies and the atmosphere in Russia were valuable to British readers back home. During this second stay in Russia, Keon made the acquaintance of Jacques Boucher de Perthes, a notable French antiquarian and writer. Boucher de Perthes later included warm recollections of his meeting with Keon in his own travel memoir Voyage en Russie (1859), testifying to Keon’s personable character and intellectual camaraderie abroad. By the late 1850s, Miles Gerald Keon had thus built a multifaceted literary career: he was a respected newspaper correspondent, a magazine editor, an author of pamphlets and saintly biographies, and a published novelist. He also occasionally contributed to other periodicals of the day – for example, he wrote articles for Colburn’s New Monthly Magazine and the Dublin Review, reflecting his ongoing engagement with literary and Catholic scholarly circles.

In 1858, a new opportunity – albeit a short-lived one – took Keon beyond Europe. He traveled to Calcutta, India, having been invited (or so he believed) to take up the editorship of the English-language newspaper Bengal Hurkaru. Unfortunately, this venture turned out to be misbegotten; Keon later described it as an appointment made “under a mistaken arrangement.” It appears there was a misunderstanding or change of plans regarding the editorial position, leaving Keon without a post in Calcutta. After a brief stay in India in 1858, he returned to England by early 1859, his journalistic prospects temporarily in limbo.

Colonial Secretary in Bermuda and Later Years

Upon his return from India, Keon’s career took a decisive turn from journalism to colonial administration. In March 1859, with the patronage of Sir Edward Bulwer-Lytton, Keon was appointed Colonial Secretary of Bermuda. Bulwer-Lytton – himself a famous novelist and, at that time, Secretary of State for the Colonies – recognized Keon’s talents and perhaps his loyalty to the Crown, facilitating this appointment. The position of colonial secretary was a senior post in the small British colony: Keon became the chief administrative officer to the Governor of Bermuda, responsible for governmental correspondence and oversight of civil affairs. For Keon, then 38 years old, this was a significant career shift and a stable, salaried role after years in the volatile world of newspapers. He relocated to Hamilton, Bermuda in 1859 and would reside there for the remainder of his life.

Settling in Bermuda did not mean the end of Keon’s literary pursuits. He continued to write while fulfilling his administrative duties. In 1866, he published his second and most ambitious novel, Dion and the Sibyls: A Romance of the First Century. This work, released in two volumes, was a historical novel set in ancient Rome and the Holy Land during the early Christian era. Dion and the Sibyls follows the adventures of Dion (portrayed as the future Saint Dionysius the Areopagite) and interweaves pagan prophecy (the Sibyls) with the coming of Christianity. The novel’s aim was to depict the spiritual hunger of the pagan world and the profound impact of Christ’s appearance. Notably, Keon dared to include a brief fictional encounter with Jesus Christ near the end of the story – a bold literary choice that few novelists would attempt. Dion and the Sibyls was well-received in Catholic circles and even marketed as a “classic Christian novel,” with one American Catholic review classing it alongside Cardinal Wiseman’s Fabiola and Newman’s Callista – a high compliment in the realm of religious fiction. An American edition was published by the Catholic Publication Society in New York in 1871, attesting to its transatlantic appeal.

Beyond writing, Keon remained active in public discourse. In early 1867, he delivered a series of lectures in Bermuda, demonstrating that his interest in politics and philosophy had not waned. These talks, given at Mechanics’ Hall in Hamilton, were on the theme of “Government: its Source, its Form, and its Means.” Over several evenings, Colonial Secretary Keon addressed local audiences on the origins of governmental authority, different forms of government, and how government can best achieve its ends. His erudition and eloquence were evident, and the lectures were likely informed by both his classical education and his practical experience in administration. The following year, Keon was invited to undertake a lecture tour in the United States, which suggests that his reputation as a compelling public speaker had spread beyond Bermuda. However, he declined the U.S. lecture invitation, citing his obligations as a colonial official. Keon was conscious that accepting speaking engagements abroad might conflict with his duties or pose diplomatic sensitivities given his position.

In December 1869, on the eve of a momentous event for the Catholic Church, Keon took a leave of absence from his post in Bermuda to travel to Rome. There he attended the opening session of the First Vatican Council (Vatican I) at St. Peter’s Basilica. This council, convened by Pope Pius IX, was historic for defining the dogma of papal infallibility. Keon’s presence in Rome at the Council’s start underscores his deep engagement with his faith and his desire to witness church history in the making. It also provided an occasion for him to reconnect with the wider Catholic intellectual community in Europe.

After this Roman sojourn, Keon returned to Bermuda and resumed his colonial secretary duties. He would continue to serve diligently in Bermuda’s civil administration into the 1870s. By this time he was a respected figure in the island colony, known not only as a high-ranking official but also as a learned man who had published noteworthy works. Contemporary accounts suggest that Keon was well-regarded in Bermuda society; he was even asked to head a committee for an international event (the Bermuda participation in the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition, although this would occur after his death).

Miles Gerald Keon died in office on 3 June 1875 in Hamilton, Bermuda, at the age of 54 after a short illness. His passing was noted both in Bermuda and abroad. With his death, “the last of the Keons of Keonbrooke” was gone. He left no surviving children to carry on the family name or line, thus closing a lineage that had been part of Leitrim’s minor aristocracy. Keon was buried in Bermuda; an obituary in the Royal Gazette (Bermuda) lamented the loss of the long-serving colonial secretary and noted that he was survived by his wife, Anne. His life had spanned continents – from Ireland and England to France, Algeria, Russia, India, and finally the Atlantic isles of Bermuda – a trajectory not common in the 19th century and reflective of the global reach of the British Empire coupled with the restlessness of an intellectual mind.

Major Publications

Keon’s diverse writings include political essays, fiction, and historical/religious works. His major publications and writings include:

- The Irish Revolution; or, What Can the Repealers Do? And What Shall Be the New Constitution? (pamphlet, 1843) – A political tract discussing Ireland’s Repeal movement and proposing constitutional reforms. It was one of Keon’s first forays into print, evidencing his early nationalist and analytical interests.

- The Jesuits (article, Oxford and Cambridge Review, September 1845) – An unsigned article in an academic journal that robustly defended the Jesuit order. Its publication in a university review and the controversy it stirred led to the piece being reprinted as a separate pamphlet. This bold apologetic work bolstered Keon’s reputation in Catholic circles.

- The Life And Times Of The Roman Patrician Alexis (book, 1847) – A biographical account of Saint Alexis of Rome. This work reflected Keon’s interest in Catholic hagiography and the virtues of early Christian saints. Published in London, it contributed to the 19th-century revival of Catholic devotional literature.

- Harding the Money-Spinner (novel, serialized 1852; book publication 1879) – A novel of Victorian life focusing on a cunning financier named Harding. First released in serial form in The London Journal, it catered to popular tastes with themes of money and morality. The story was posthumously published in three volumes in 1879 by Richard Bentley, bringing Keon’s work to a wider book-reading audience.

- Dion and the Sibyls: A Romance of the First Century (novel, 1866) – Keon’s most acclaimed literary work, a two-volume historical novel set in the time of the Roman Emperor Augustus and the dawn of Christianity. Blending meticulous historical detail with imaginative storytelling, Dion and the Sibyls explores the yearning for a savior in the ancient world and features appearances by historical figures as well as a brief, reverent depiction of Jesus Christ. It earned praise as a significant Christian novel of its era.

In addition to the above, Keon wrote numerous articles and essays. His series of travel and military sketches for Colburn’s United Service Magazine (1845–46) are noteworthy, as are his educational “Lessons in French” in Cassell’s Working Man’s Friend (1851). He also contributed journalism to the Morning Post (including foreign correspondence from Russia) and occasional pieces to other periodicals like the New Monthly Magazine and the Dublin Review. Through these varied publications, Keon made his mark both as a commentator on contemporary issues and as a storyteller engaging with history and faith.

Critical Reception

During his lifetime, Miles Gerald Keon’s writings received a mixed but often favorable reception, particularly within Catholic and conservative circles. His 1845 Jesuit vindication article was highly controversial among Anglicans and others, but the very fact that it caused a public stir attested to its impact. The piece drew rebuttals and debate, and its reprinting suggests that it found a substantial readership curious or sympathetic to Keon’s arguments. Keon’s stance in defense of a then-unpopular religious order marked him as a bold polemicist unafraid of criticism.

Keon’s two novels each garnered attention in their own spheres. Harding the Money-Spinner, appearing serially in a popular magazine, was likely enjoyed by general readers of penny fiction, though it did not attract significant literary analysis. It can be seen as a commercially driven work that added to Keon’s popularity if not his critical acclaim. In contrast, Dion and the Sibyls was aimed at a more discerning audience and achieved considerable critical praise in Catholic literary forums. A review in The Catholic World (1871) lauded Dion and the Sibyls as “a work of uncommon merit,” comparing it to Cardinal Wiseman’s Fabiola and John Henry Newman’s Callista – which the reviewer noted was “the highest compliment we could possibly pay” to a Christian historical romance. The same review declared Keon’s novel “a dramatic and philosophical masterpiece,” commending its vivid re-creation of the Roman world and its profound religious insight. The critic singled out Keon’s daring inclusion of a portrayal of Jesus, observing that while many authors fail when attempting to depict Christ, “Mr. Keon’s bold effort pleases us so much” – implying that Keon handled the subject with reverence and skill. Such positive assessments from Catholic reviewers indicate that Dion and the Sibyls was seen as a significant contribution to Catholic literature, capable of edifying readers and countering more skeptical works (the reviewer even suggested that works like Keon’s could help counter the influence of Ernest Renan’s skeptical Life of Jesus in popular culture).

Despite these accolades, Keon never became a household name in mainstream Victorian literary society. His work was somewhat niche – appealing largely to Catholic and conservative audiences – and he did not produce a large volume of fiction. Nonetheless, within his niche, he enjoyed recognition and respect. The Dublin Review echoed positive notes about some of his writings, and his journalism in the Morning Post was valued by that paper’s readership. His contemporaries knew him as a learned and eloquent man; for instance, Boucher de Perthes’s friendly reminiscences show that Keon was personally well-regarded among fellow intellectuals. Furthermore, Keon’s unique combination of roles – as both a novelist and a colonial official – drew interest. In 1886, a decade after his death, the Stonyhurst Magazine ran two articles titled “A Colonial Secretary” reminiscing about Keon’s career, indicating that his alma mater took pride in his accomplishments. Overall, critical reception of Keon’s work in his lifetime was characterized by admiration in Catholic and loyalist circles, and a relative obscurity in others. He was seen as a talented writer who perhaps never fully broke into the upper echelons of literary fame, yet left behind work that was cherished by a devoted readership.

Recognition and Legacy

Recognition during Keon’s lifetime: Throughout his career, Miles Gerald Keon gained recognition both in the literary world and in government service. In journalistic circles, he was esteemed enough to be entrusted with high-profile assignments (such as reporting from imperial Russia) and to serve as editor of a respected Catholic magazine. Influential figures took note of him: most significantly, Sir Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s support in 1859 showed that Keon’s abilities were acknowledged at the highest levels of the British establishment. In Catholic intellectual communities, Keon was regarded as a noteworthy author – his name appeared alongside other prominent Catholic writers of the 19th century. The warm critical reception of Dion and the Sibyls and its comparison to works by Cardinal Wiseman and Newman illustrate the esteem afforded to Keon’s fiction by his contemporaries. Within Bermuda, Keon was a prominent public figure due to his position; he was essentially the right-hand man to a succession of colonial governors. Local archives and newspapers (like the Royal Gazette) recorded his contributions to the island’s administration and civic life, suggesting he was well respected in the colony. By the time of his death, Keon had carved out a reputation as an erudite colonial official who also had a literary pedigree – an unusual combination that made him something of a Victorian Renaissance man.

Posthumous legacy: After his death, Keon’s legacy lived on through his writings and the records of his life. He was accorded a place in the classic reference works of the English-speaking world. In 1892, a biographical entry on Miles Gerald Keon appeared in the Dictionary of National Biography (DNB), attesting that his life was deemed of sufficient note to be recorded for posterity. The DNB entry highlighted his status as “novelist and colonial secretary” and detailed his career, preserving his story for future generations. Similarly, the early 20th-century Catholic Encyclopedia included an article on Keon, written by Jarvis Keiley in 1911, which summarized his life and praised his contributions as a journalist, novelist, and lecturer. More recently, modern scholarship has remembered Keon in the context of Irish literature and history; for example, the Dictionary of Irish Biography notes him as “the last of the Keons of Keonbrook” and records his literary output and colonial service. Such entries ensure that researchers and readers can rediscover Keon’s story long after his time.

Keon’s literary works, especially Dion and the Sibyls, have occasionally been revisited by students of Victorian religious fiction. While not widely read today, Dion and the Sibyls is sometimes cited as an early example of a Catholic historical novel in English, noteworthy for its ambition and imaginative scope. The novel’s inclusion of theological and philosophical themes, and its daring portrayal of sacred history, mark it as a precursor to later religious fiction that attempts to bridge faith and literature. In Bermuda, Keon is remembered as part of the island’s colonial heritage. His 16-year tenure as Colonial Secretary spanned a significant period in the mid-19th century, and he would have played a key role in implementing policies and maintaining the daily operations of government there. Though no monument or public memorial is known to exist for him in Bermuda, his name appears in historical records and governmental archives, and the story of a literary man serving as a top colonial administrator adds a human dimension to Bermuda’s history.

In summary, Miles Gerald Keon’s impact lies in the unique intersection of his talents and roles. He left behind writings that captured aspects of the 19th-century Catholic experience and adventurous travel, and he served with distinction in the British colonial system. His life is an example of how an Irish Catholic in the Victorian era navigated the worlds of literature, journalism, and empire. Keon’s legacy endures in the pages of the books and articles he wrote and in the biographical accounts that continue to recognize him as a noteworthy figure of his time. His work – once praised as “a masterpiece” – and his story as a globe-trotting intellectual and civil servant remain a small but intriguing part of 19th-century history, illustrating the rich tapestry of Irish contributions to literature and public life across the British world.

Works

Books

- The Life And Times Of The Roman Patrician Alexis (1847)

- Harding the Money-Spinner (1852)

- Dion and the Sibyls: A Romance of the First Century (1866)

Poems

- * Coronation Ode (1838)

- * The Last Battles and Death of King Charles Albert (1849)

- * The Plague Comes, and the Plague Goes (1849)

- * The Voyage of the Air (1849)

- * Hougoumont: The First—Last Meeting (1853)

- * The Spectre of the ‘Golden Boy’ (1854)

Other Works

- The Talleyrandism of the Drawing-room (1841)

- The Irish Revolution; or, What Can the Repealers Do? And What Shall Be the New Constitution? [pamphlet] (1843)

- Notre Dame des Victoires [essay] (1845)

- The Jesuits [essay] (1845)

- The Late Struggles of Abd-el-Kader, and the Campaign of Isly [article series] (1845)

- An Idler’s Journey on Foot through France [essay] (1846)

- The Catholic Man of Letters in London; a History of Nowadays, inscribed to the New Generation [essay] (1846)

- The Expediency of Transferring the Holy See to Leeds [essay] (1846)

- To the Catholics of Great Britain and Ireland, and the unprejudiced public [essay] (1846)

- Holy Week at Oscott [essay] (1847)

- Pope Gregory XVI and the Conversion of England [essay] (1847)

- A Letter on the Greek Question (1850)

- Lessons in French [article series later published by Cassell] (1851)

- Voltaire: What he was, and what he contributed to accelerate [essay in Morning Post] (1856)

- The Wedding Ring: A Ghost Story (1858)

- Government, its Source, its Form, and its Means [lectures published posthumously]

References

- Catholic Answers. (2019, February 22). Miles Gerald Keon. Catholic Answers. https://www.catholic.com/encyclopedia/miles-gerald-keon

- The Catholic Publication House. (1871). Keon’s Dion and the Sibyls. In The Catholic World: A Monthly Magazine of General Literature and Science (Vol. XIII, Ser. April to September, pp. 429–430). essay. Retrieved July 1, 2025, from https://readingroo.ms/4/8/4/4/48448/48448-h/48448-h.htm#Page_429.

- Gerard, J. (1894). Some Stonyhurst Men. In Stonyhurst College, its life beyond the seas, 1592-1794 and on English soil, 1794-1894 (pp. 233–235). essay, Marcus Ward & Co. Retrieved July 1, 2025, from https://archive.org/details/stonyhurstcolle00geragoog/page/n252/mode/2up.

- * Hatt, J. B. (1886, March). A Colonial Secretary – Part I. Stonyhurst Magazine, XXIV, 203–207.

- * Hatt, J. B. (1886, June). A Colonial Secretary – Part II. Stonyhurst Magazine, XXVI, 254-258.

- Joseph, G. (1895). Keon, Miles Gerald. In A literary and biographical history or bibliographical dictionary, of the English Catholics, from the breach with Rome, in 1534, to the present time (Vol. 4, pp. 17–24). essay, Burns & Oates. Retrieved July 1, 2025, from https://archive.org/details/literarybiograph04gilluoft/page/n25/mode/2up.

- Kent, C. (1909). Keon, Miles Gerald (1821-1875). In The Dictionary of National Biography (Vol. XI, pp. 35–36). The MacMillan Company. Retrieved July 1, 2025, from https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_Gio8AAAAIAAJ/page/34/mode/2up.

- O’Donoghue, D. J. (1912). Keon, Miles Gerald. In The poets of Ireland; a biographical and bibliographical dictionary of Irish writers of English verse (p. 233). Hodges Figgis & Co. Retrieved July 1, 2025, from https://archive.org/details/cu31924029566530/page/232/mode/2up.

- Sutherland, J. (2009). In The Longman Companion to Victorian Fiction (2nd ed., pp. 351–352). Pearson Education. Retrieved July 1, 2025, from https://archive.org/details/longmancompanion0000suth/page/350/mode/2up.

- Woods, C. J. (2009). Keon, Miles. Dictionary of Irish Biography. https://www.dib.ie/biography/keon-miles-a4518

* Work or reference hosted on Leitrim Books.