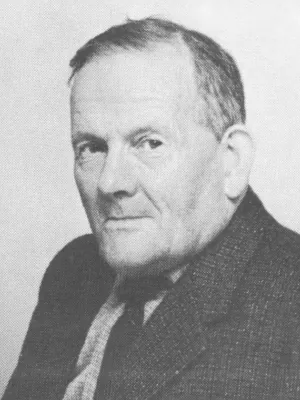

Padraic J. O’Rourke

Biography

Early Life and Personal Background

Padraic (Patrick) Joseph O’Rourke was born on 7 March 1903 on a farm in Gortnaderrary, near Kiltyclogher, County Leitrim. He was the son of Francis O’Rourke and his wife, Ellen (née O’Rourke). Raised in this rural, mountainous corner of northwest Leitrim – a borderland region adjoining County Fermanagh – O’Rourke grew up steeped in the traditions of Irish rural life. This upbringing would form the cornerstone of both his identity and his creative inspiration. He often spoke of his “first love” being for farming, and his affection for the land was a persistent influence on his poetry. He once recalled composing his first poem—some sixteen verses long—while taking turns at the butter churn, a common task in his youth. Though he would go on to publish hundreds of poems and articles, that early act of composition rooted his writing in the rhythm and imagery of the Irish countryside.

On 27 April 1939, he married Catherine Keany in the Church of Ballaghameehan, and together they raised a large family.

Career in Journalism

O’Rourke had a long career as a regional journalist, contributing to a wide array of Irish newspapers, including the Leitrim Observer, Fermanagh Herald, Donegal Democrat, Longford Leader, Irish Press, Leitrim Leader, and The Weekly News (Belfast). His contributions ranged from poetry and feature writing to the much-loved “little bits of news” that captured the pulse of life in North Leitrim. In one widely shared anecdote, a soldier stationed in India wrote to O’Rourke after reading one of his “Kilty Notes” in a stray copy of the Leitrim Observer—an item about an outsized three-pound potato found on a local farm. The soldier said the news made him feel at home in a faraway land. This anecdote, warmly recounted in his obituary, captures the quietly enduring influence of his writing on the worldwide Irish community.

O’Rourke’s byline also appeared in the Sligo Champion on occasion – for example, he penned a 1939 review in that paper of a new Irish play (Paddy Reilly from Ballyjamesduff, a two-act comedy by Alfred G. McGovern), bringing to it his insight into rural Irish characters and the emigrant experience. His journalism was marked by an engaging, down-to-earth style that reflected both the concerns of his community and his own literary sensibilities.

O’Rourke also had a deep sense of historical consciousness. In 1966, he composed the verse for the memoriam card of Sean Mac Diarmada, a native of the same parish and one of the executed leaders of the 1916 Rising. His poetry regularly reflected both nationalistic pride and regional loyalty.

Poetry and Publications

While earning regard as a local newsman, O’Rourke became even more widely known for his poetry, writing nearly 500 poems in his lifetime. He wrote under the name Padraic J. O’Rourke, and his verses were published in numerous Irish newspapers and magazines from the 1920s through the 1970s. Many of his poems appeared in national and regional papers such as the Irish Independent, the Sligo Champion, and later in the annual The Leitrim Guardian magazine. His talent was recognized early: O’Rourke won the Irish Independent’s weekly Irish Verse contest on multiple occasions. Notably, in 1931 his poem “The Poet” earned that newspaper’s prize, and he repeated this achievement with “The City Dweller on Holiday” in 1936 and “December Gifts,” a Christmas-themed lyric, in 1947. Such honors attest to the polish and popular appeal of his verse, which often stood out among the numerous submissions.

O’Rourke’s poetry is traditional in form, heartfelt in tone, and steeped in the ethos of rural Ireland. He favored regular meters and rhymed stanzas, crafting verses that were easy to read aloud and memorize. His language is clear and evocative, frequently painting vivid pastoral images or invoking emotional memories. Common themes in O’Rourke’s oeuvre include the simple pleasures of rural Irish life, the beauty of nature, patriotic sentiment and Irish nationalism, deep Catholic faith, longing memory of times and loved ones past, and the sorrows and consolations of emigration. There is often a direct emotional appeal in his lines – whether celebrating homeland joys or lamenting losses, his voice speaks plainly to the reader’s heart.

“The Old Boreen”

One of O’Rourke’s well-known poems is “The Old Boreen,” published in The Leitrim Guardian in 1975. (In Hiberno-English, a boreen means a little country road, usually winding through the countryside.) This nostalgic ballad is narrated by an elderly man recalling a youthful summer romance on a quiet Irish lane. In warm, golden-hued imagery, the poem’s opening lines describe how “We stood together and watched the sheen / Of the setting sun thro’ the alder branches / That intertwined o’er the old Boreen”. The speaker and his “laughing colleen” (young girl) pledged their love under the twilight sky, imagining “long joy-filled days before us / As night crept into the old Boreen”. O’Rourke’s gentle rhymes and descriptions of birdsong and sunset create an idyllic portrait of first love.

However, “The Old Boreen” is not merely a reverie of innocent youth – it is also an elegy for love lost to emigration, a fate common in 20th-century Ireland. The young woman in the poem leaves “on a summer morning… / Across the wave there was full and plenty” abroad, seeking a better life, and she never returns. The later stanzas convey the speaker’s enduring heartbreak and devotion. Decades have passed without word of his beloved, and now “I am old and gray, and so very lonely, / My vows I’ve kept, for what might have been” had she not gone away. The once-bright boreen is now a place of ghosts and memories. Through this contrast, O’Rourke movingly explores the personal cost of emigration: the boreen becomes a symbol of both cherished memory and lingering sorrow. The poem’s simple quatrains and sincere voice make its emotional impact especially potent.

“Elegy for the Leaves”

Another standout work is “Elegy for the Leaves,” also published in The Leitrim Guardian in 1975. In this lyric O’Rourke turns to nature to reflect on aging, loss, and the promise of renewal through art. “Elegy for the Leaves” personifies the autumn trees as grieving parents about to lose their leaves to winter. No comforting breeze or birdsong can allay their sense of doom:

No wind can blow the grief awayOf trees whose leaves must wither soon,No song of bird, of sunshine ray,Can banish dread of Winter moon.

The poem’s tone is mournful and contemplative, as O’Rourke laments the inevitable decay that comes with time – a clear metaphor for mortality and the fading of youth (or perhaps for the waning of one’s creative powers with age).

Yet, true to the resilient spirit in much of O’Rourke’s writing, the elegy finds a note of solace by its conclusion. After bidding farewell to the fallen leaves and the departed summer’s beauty, the speaker offers a gentle benediction. He urges the leaves to “sleep well” and suggests that from their decayed remains – “the dust of dreams” – may spring new inspiration:

Sleep well and form the dust of dreamsInspire some poet’s grandest layWhen Winter’s unheeding gleamsAnd Summer seems so far away.

These lines, which imagine future poetry arising from the death of the old leaves, give the piece a self-reflexive twist: O’Rourke implies that art and memory can rejuvenate what winter has withered. With its vivid personification and melancholic imagery of “yellowing leaves” and “the blackbirds’ merry tune” growing hushed, “Elegy for the Leaves” exemplifies O’Rourke’s gift for finding profound emotional resonance in the cycles of nature.

Themes, Style, and Other Works

Across his body of work, O’Rourke consistently celebrated the landscape and people of his native Ireland. His verses often rejoice in pastoral life and the freedom of the countryside. In “The Shuiler’s (Wanderer’s) Song” for instance, the poet contrasts the contentment of a roving poor man with the burdens of the rich.

What wealth can equal the broad green fieldsWhen the drowsy stillness of summer reigns…I have no fears for the days to be,No vain regrets for the years behind.

“And I envy not the rich man his wine… / I would never exchange his drink for mine” declares the carefree vagabond narrator. O’Rourke’s sympathy clearly lies with the simple joys of nature over material “worthless gold”. Likewise, in “The City Dweller on Holiday,” a homesick clerk revels in escaping Dublin’s grind for the wild beauty of the west:

What wondrous magic stirs my soulAs down the green boreens I stray;In careless happy mood I stroll,And e’en the lark is not more gay.My pulses throb with radiant life,Queen June now reigns o’er mount and glen;Her soft voice pierced the City’s strife–I heard, and left my desk and pen.

The poet invites readers to share in this almost spiritual rejuvenation found in nature’s tranquility.

Nationalism and love of country are recurring currents as well. Writing in the decades surrounding Irish independence, O’Rourke often infused his work with patriotism. Some poems address Ireland’s political struggles overtly: in “Go Easy, Mr. Warnock” (1948), a sharp reply to a Northern Ireland politician, O’Rourke voices the fervent hope for an end to Partition. He asserts that no true Irishman “[desires] to be linked with Britain’s Crown,” and predicts “the ‘Wee Six’ will soon be merging in a very real Free State – / A Republic for Ireland’s Thirty-Two” (a reference to uniting the six counties of Northern Ireland with the twenty-six of the Republic). Even in less overtly political works, a subtle nationalist pride shines through – as in his elegy “Arranmore,” which mourns drowned island emigrants but pointedly calls them “proud Gaels” steeped in “Gaelic lore,” praying that Christ “solace dearly Arranmore” in its hour of grief. Such lines reveal O’Rourke’s heartfelt connection to Ireland’s people and heritage.

Religion and devotion are equally prominent in O’Rourke’s poetry, reflecting the central role of Catholic faith in mid-century rural Ireland. He wrote numerous poems on holy days, Christmas customs, and Irish saints. In “The Miracle,” a Christmas Eve reverie, he imagines the Virgin Mary smiling in blessing at a village child’s humble gift: “The Virgin Mother smiled and bowed her head. / Such a sweet smile, ’twould save a soul from wreck.” Another poem commemorates Blessed Oliver Plunkett, the 17th-century Irish martyr, praising the saint who “walked the road Christ pressed with bleeding feet” and “to death most cruel he did meekly bow” out of love for Ireland and God. O’Rourke’s religious verses often blend reverence with patriotism, presenting piety and Irish identity as mutually reinforcing virtues. Even his Christmas poems frequently include prayers for emigrants overseas, linking faith to the memory of absent loved ones.

Indeed, the pain of emigration and exile is a leitmotif that runs through much of O’Rourke’s work, undoubtedly influenced by the depopulation of rural Ireland in his time. Poems like “The Old Boreen” already show how leaving home can break hearts. In “Wind of the West,” published during the mid-20th century wave of emigration, O’Rourke addresses the Atlantic wind as a messenger carrying “memories of home that are tenderest and best” to those far away. He writes with compassion of “friends across the sea / Who yearn for such a night as this”, especially in pieces like “Christmas Eve in Ballagh”, which evokes the bittersweet mix of joy and sadness each Christmas when expatriates are remembered in their absence. Through these poignant themes, O’Rourke became a poetic voice for the Irish diaspora experience as well as for those who remained in the old country.

Stylistically, Padraic J. O’Rourke was a traditionalist. His verse forms harkened back to the late 19th-century and early 20th-century Irish poets and balladeers. He favored melodic meters, end-rhymes, and accessible diction over modernist experimentation. This conservative style did not limit his range of expression, however. He could be gently humorous and satirical – for example, in “Vitamins” (1947) he wittily lampoons the government’s failed promises during wartime rationing, joking that “Ministers pelt us with excuses… / The vigorous methods they apply / Are wiping out the population.” He could also be elegiac and tender, as seen in memorial pieces and in the sensitive nature imagery of his late poems. What unifies his diverse pieces is a direct emotional sincerity. Whether he was invoking the sound of the “wild bees hum” and “blackbird sings” in a summer field or calling for Ireland’s freedom, O’Rourke wrote in a way that ordinary readers could connect with immediately. His imagery – holly berries and curlew’s cries, quiet lanes and cottage hearths – was drawn from the familiar world around him, and his messages were clearly stated from the heart. This combination of vivid imagery, heartfelt theme, and musical form gave his poetry a lasting appeal among local audiences.

Later Years and Legacy

Padraic J. O’Rourke continued to write and remain active in literary circles well into his later years. He contributed poems to The Leitrim Guardian in the 1970s, including some of his finest mature work as discussed above. In these final decades he achieved a kind of elder-statesman status in his community – a respected journalist-poet whose writings recorded the dreams and values of a generation. O’Rourke died at his home near Kiltyclogher on Holy Saturday, 5 April 1980, at the age of 77. His funeral was held on Easter Monday, with a reading of one of his poems delivered by Fr. Hannon. In its obituary notice, the Leitrim Observer described him as a “well-known Leitrim writer and poet,” paying tribute to his lifetime of letters. He was laid to rest in the cemetery adjoining St. Patrick’s Church in Kiltyclogher, in the soil of the parish that had nurtured his imagination.

Though he never published a book-length collection in his lifetime, O’Rourke’s legacy endures in the pages of Irish newspapers and local journals where his verses appeared, and in the fond memory of the community he served. His poetry – rich with the lore of Leitrim’s fields, the faith of its people, and the voice of its boreens – stands as a lyrical chronicle of 20th-century rural Irish life. Today Padraic J. O’Rourke is remembered as a gifted regional poet-journalist who captured the hopes and heartbreaks of his homeland in lines of simple beauty and sincere feeling.

Works

Poems

- The Shuiler’s Song (1933)

- Blessed Oliver Plunkett (1935)

- Arranmore (1935)

- The City Dweller on Holiday (1936)

- Vitamins (1947)

- Go Easy, Mr. Warnock (1948)

- Wind of the West (1956)

- Christmas Eve in Ballagh (1971)

- The Poor Man’s Christmas (1971)

- Kiltyclogher (1974)

- The Miracle (1974)

- Elegy for the Leaves (1975)

- The Old Boreen (1975)

- The Peace Marchers (1977)

- Christmas Thoughts (1984)

References

- Death of Well-Known Leitrim Writer and Poet. (1980, April 12). Leitrim Observer, pp. 1, 5.

- O’Rourke, P. J. (1933, October 21). The Shuiler’s Song. Sligo Champion, p. 7.

- O’Rourke, P. J. (1934, December 22). The Miracle. Frontier Sentinel, p. 6.

- O’Rourke, P. J. (1935a, June 8). Blessed Oliver Plunkett. Sligo Champion, p. 2.

- O’Rourke, P. J. (1935b, December 7). Arranmore. Sligo Champion, p. 9.

- O’Rourke, P. J. (1936, August 1). The City Dweller on Holiday. Irish Independent, p. 3.

- O’Rourke, P. J. (1947, February 8). Vitamins. Sligo Champion, p. 2.

- O’Rourke, P. J. (1948, December 4). Go Easy, Mr. Warnock. Frontier Sentinel, p. 5.

- O’Rourke, P. J. (1956, August 11). Wind of the West. Sligo Champion, p. 7.

- O’Rourke, P. J. (1971). Christmas Eve in Ballagh. The Leitrim Guardian. Retrieved June 22, 2025, from https://leitrimdoc.ie/leitrim-guardian-journal-1969-1999/.

- O’Rourke, P. J. (1975a). Elegy for the Leaves. The Leitrim Guardian, 33. Retrieved June 22, 2025, from https://leitrimdoc.ie/leitrim-guardian-journal-1969-1999/.

- O’Rourke, P. J. (1975b). The Old Boreen. The Leitrim Guardian, 20. Retrieved June 22, 2025, from https://leitrimdoc.ie/leitrim-guardian-journal-1969-1999/.