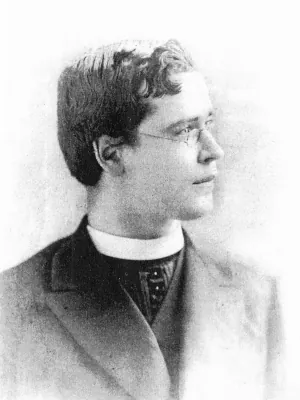

Rev. James Keegan

Biography

Early Life

James Keegan was born January 1859 to William Keegan and Mary Curran in Racullen townland, parish of Cloone, Co. Leitrim. Raised in a devout rural Irish community, Keegan early on absorbed the rich oral traditions and nationalist sentiments of post-Famine Ireland. He pursued ecclesiastical studies at St. Patrick’s College, Carlow, a seminary renowned for training missionaries for English-speaking countries. There he excelled academically and nurtured a lifelong passion for Irish history and literature. Keegan was ordained a Catholic priest in May 1883. Soon after ordination, he embarked on a journey that would define his career – and his literary legacy – by leaving Ireland for the United States.

Emigration and Clerical Career

In late 1883, newly ordained Rev. Keegan emigrated to America to serve the growing Irish diaspora. He was received into the Archdiocese of St. Louis, Missouri, where there was great need for Irish-speaking clergy. By 1885 he was assigned as a curate at St. Malachy’s Church in St. Louis, a large Irish-American parish, where he ministered for roughly eight years (1885–1893).

During these years in America, Keegan also emerged as an intellectual and community leader among Irish émigrés. He balanced his clerical responsibilities with a parallel vocation as a writer and cultural advocate. He contributed regular articles and poetry to Irish-American Catholic periodicals, becoming, as one magazine noted, “a contributor of graceful poems and interesting prose sketches” to Donahoe’s Magazine of Boston and other journals. Based in a vibrant Irish enclave in St. Louis, Rev. Keegan also lectured on Irish history and current affairs, inspiring pride in Irish heritage among immigrants. His personal experience bridging Ireland and America lent authority to his voice on issues facing the Irish diaspora. Notably, he lamented how poorly prepared many Irish emigrants were “for commencing life in strange lands,” blaming “inexcusable sloth on the part of those who should train and educate them”. Such frank commentary, coming from a priest with one foot in each world, exemplified Keegan’s dedication to improving the lot of his people both spiritually and culturally.

Literary Contributions

While tending to his parish, James Keegan quietly built a reputation as a poet, essayist, and translator. Nearly all of his writings were devoted to Irish themes, reflecting his deep love for Ireland’s language, history, and folklore. He published under his own name in various reputable outlets. For example, in June 1885 the prestigious New York–based journal Catholic World featured his lyrical tale “St. Columbkille and the Mower,” a short piece blending hagiography and rustic legend. In Boston’s Donahoe’s Magazine, Keegan’s byline appeared on poems and on scholarly essays defending Irish culture. A contemporary profile from 1887 noted that Rev. Keegan had already produced numerous poems distinguished by “their Irish spirit,” and it singled him out as both a patriot priest and poet. One of his celebrated verses, “The Bards of Old,” glorified the ancient Gaelic bards and Ireland’s heroic age. Another poem, “You’re Welcome, Mick McQuaid,” written in a jovial vernacular style, humorously greeted a popular fictional Irish character – showcasing Keegan’s range from high mythic imagery to playful satire.

Keegan also engaged in translating and adapting Gaelic-language lore. He was well versed in Old Irish literature, and he leveraged this knowledge in his writing. Notably, he corresponded with Dr. Douglas Hyde (An Craoibhín Aoibhinn), who would later be the first President of Ireland, on matters of Gaelic literature. Hyde, a leading figure of the Irish literary revival, counted Keegan as a friend and “accomplished scholar”. In Hyde’s seminal Literary History of Ireland (1906), he credits Rev. Keegan with translating obscure Irish saga material for him – evidence of Keegan’s scholarly contributions behind the scenes. Keegan’s own translations of Irish folktales and legends into English circulated in manuscript and may have been read at cultural gatherings. A story titled “The Two Hunchbacks” and a comic folktale “The Goblin Dance at Corriga Crossroads” (Corriga being a townland near his home) are attributed to his pen in later collections. Through such works, Keegan helped make the Gaelic mythic heritage accessible to English-speaking audiences in Ireland and America.

Rev. Keegan’s writings appeared in a variety of publications and anthologies of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In his lifetime, he wrote not only for Donahoe’s Magazine but also for The Current and the Western Watchman (a St. Louis Catholic paper), among others. After his death, his verse was cherished by the Irish-Irish and Irish-American communities. His poems were included in anthologies such as Daniel Connolly’s The Household Library of Ireland’s Poets (1887) and T. D. Sullivan’s Irish National Poems (1911), often accompanied by biographical notes honoring him as a “patriot priest”. A Chicago-based anthology Rhyme with Reason: A Garland of Irish Shamrocks (1910) reprinted several of his works – from nationalist rallying cries to tender nostalgic pieces – ensuring that Rev. James Keegan’s voice remained part of the Irish literary revival canon even decades after his passing.

Role in the Gaelic League and Irish Renaissance

Rev. Keegan played an active if somewhat behind-the-scenes role in the movement that came to be known as the Gaelic Revival or Irish Renaissance. In the 1880s, years before the formal founding of the Gaelic League, Keegan aligned himself with the Gaelic Union – an earlier organization dedicated to preserving and promoting the Irish language. Writing from America, he championed the revival of Gaelic with zeal. He was “an enthusiast in the movement for the study of the Irish language” and used his influence to rally support across the Atlantic. In 1886 the Gaelic Journal (the Union’s official publication) reported that at a council meeting in Dublin, a letter from Rev. Keegan of St. Louis was read aloud: in it he enclosed a donation of $5 (a significant sum at the time) and “promised to contribute the same sum monthly,” challenging all Irish clergymen, lawyers, and professionals to do likewise in support of the Irish-language journal. This public challenge created a stir – here was a young emigrant priest shaming Ireland’s own elites into action for their heritage. The Gaelic Journal praised Keegan’s letter for “telling many truths” that some in Ireland “would not wish told” about cultural neglect. He bluntly contrasted the Irish, who had allowed their ancestral language and literature to languish, with the Germans, who painstakingly researched and published Ireland’s medieval manuscripts that “we ourselves had left rotting for ages”. Such commentary underscored the sense of urgency and mission that infused Keegan’s work in the Gaelic revival.

When Douglas Hyde and others founded the Gaelic League in 1893, Rev. Keegan was quick to lend his support. He and Hyde were kindred spirits in this cause: both believed that Ireland’s “past, history, and literature” were vital to its national consciousness. Keegan’s name is often listed among the early champions of the League’s efforts. Although based abroad, he used his writings to urge on the revival at home. He wrote passionate pieces for the Irish press extolling the value of the Irish tongue (one notable essay, “The Celtic Tongue,” was widely quoted in Ireland). He also encouraged Irish-American organizations to form language classes and libraries of Irish books. In 1893, as the Gaelic League got underway, Keegan happened to be back in Ireland on leave; he attended meetings and offered to serve as a liaison between the League and the Irish in America. Indeed, years earlier he had essentially acted as an unofficial ambassador of the Gaelic Union in the United States. Thanks to figures like Keegan, the transatlantic links of the Irish Renaissance were strong – ideas, publications, and funds flowed both ways across the ocean. Though his life was brief, Keegan is considered part of the first wave of the Irish literary revival, helping lay the groundwork for the cultural renaissance that blossomed at the turn of the century.

Use of Pseudonyms in Journalism

Despite his fervent nationalism, Rev. Keegan remained a Catholic priest bound by the strictures of his ecclesiastical superiors. Late Victorian church authorities often frowned upon priests involving themselves in politics or overt nationalistic agitation. To navigate this delicate situation, Keegan frequently wrote under pseudonyms when contributing to secular or political journals. He assumed a variety of pen names in order to express frank opinions without attracting unwanted attention from his bishop. Contemporary readers of Irish nationalist newspapers might not have realized that certain stirring poems or editorials were the work of the curate from Cloone. This subterfuge was so successful that one biographer admiringly remarked on Keegan’s “uncanny ability to favete linguis” with respect to his superiors. (The Latin phrase favete linguis, literally “favor me with your tongues,” is a classical injunction meaning “keep silent” – an apt metaphor for the discretion Keegan exercised.) For example, while he openly signed pieces in Catholic venues like Catholic World or Donahoe’s Magazine, he would adopt pen names for more politically charged contributions to Irish nationalist journals. These pseudonyms have proven hard to trace, precisely because Keegan was careful never to let his literary persona compromise his priestly position. What is clear is that he managed to write boldly in support of Ireland’s cause – advocating land reform, language revival, and national self-confidence – all while officially remaining a dutiful clergyman. This balancing act of public passion and private anonymity speaks to his character. It allowed Keegan to be, in effect, two voices in one: the gentle parish padre offering spiritual guidance, and the fiery Irish patriot stirring hearts through the printed word.

Note: In The Poets of Ireland (1912), D. J. O’Donoghue writes that Rev. Keegan “wrote for Nation, United Ireland, Weekly Freeman (of Dublin), and among American periodicals for Catholic World, Donahoe’s Magazine, N. Y. Catholic Review, Boston Pilot, Catholic Union and Times (Buffalo), Redpath’s Weekly, Western Watchman (St. Louis), Chicago Citizen, etc., frequently over signatures of ‘‘Pastheen Fionn,” “Paistin Fionn,” “Orion,” and “Macaedhagain.”

Death and Legacy

In mid-1893, after nearly a decade in America, Rev. Keegan’s health began to fail. He suffered from severe rheumatism, a condition that may have been exacerbated by the Mississippi Valley climate. Hoping to recuperate, he obtained leave to return to Ireland towards the end of 1893. He spent time taking the waters at Lucan Spa near Dublin and then went home to County Leitrim to be with his family. Sadly, his condition did not improve. On 5 January 1894, Rev. James Keegan died at his parents’ home in Cloone, at the age of only thirty-five. The news of his untimely death sent ripples through both the local community and the broader intellectual circles who knew his work. In Cloone, parishioners mourned the loss of a native son who had achieved so much abroad and returned only to be buried in the soil of his youth. His funeral in Cloone was said to be a large one, attended by neighbors who remembered “Fr. James” as a bright, compassionate young man, and by Irish language activists who revered him as a “patriot priest”.

Obituaries in Irish-American newspapers and journals celebrated Keegan’s dual legacy. The Boston Pilot recalled his humor and hospitality, while the Gaelic Journal in Dublin eulogized his devotion to Ireland’s heritage. The Gaelic Union in its annual report praised Rev. Keegan’s contributions and passed a resolution of gratitude for his work on behalf of the Irish language (in effect honoring him as a martyr of the cultural cause). Douglas Hyde, upon learning of Keegan’s death, lamented the loss of “my late lamented friend” who had been one of the very few clergymen of that era deeply learned in Gaelic scholarship. Hyde would later acknowledge Keegan’s assistance in his research, ensuring that the priest’s name lived on in footnotes of Ireland’s literary history.

In the years after 1894, Rev. Keegan’s writings continued to speak for him. Poets like Patrick Kane composed verses in his memory (Kane’s elegy “In Memory of Father Keegan” was published in Chicago in 1902). Many of Keegan’s own poems were reprinted in memorial collections, ensuring that new generations encountered his rousing calls to remember Ireland’s glory and his gentle pastoral lyrics about the “old place at home”. By the early 20th century, he was recognized in anthologies as part of the pantheon of Irish nationalist poets, alongside more famous names. Yet, as decades passed, James Keegan’s personal story drifted into obscurity even as a few of his songs survived in print. It was not until the 21st century that scholars undertook to fully study his life. In 2005, a dedicated biography The Piper of Cloone: Father James Keegan and the Early Gaelic Revival was published, representing the first full study of his “brief but active career and literary production”. This work and other research have solidified Keegan’s posthumous reputation as an influential albeit understated figure in the Irish Renaissance.

Today, Rev. James Keegan is remembered as a bridge figure between Ireland and its diaspora, between the Catholic clergy and the cultural revivalists. In his short life he exemplified the ideal of the scholar-priest patriot: preserving ancient lore, writing poetry that stirred nationalist pride, and encouraging a downtrodden people to rediscover dignity through their language and literature. Though he died young, Rev. Keegan’s legacy endures in the words he left behind and in the renaissance he helped foster – a legacy of faith, scholarship, and quiet heroism in service of Ireland.

References

- Gaelic Union. (1894). The Gaelic Journal, 1887-1889: No. 25, Vol. III – No. 32, Vol. III.

- Irish news by mail. (1893, September 30). The Pilot, p. 3. Retrieved May 27, 2025, from https://newspapers.bc.edu/?a=d&d=pilot18930930-01.2.14.

- Lyons, F. (2019). Chaos or Comrades? Transatlantic Political and Cultural Aspirations for Ireland in Nineteenth-century Irish American Print Media. Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium, 39, 191–212. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45373700

- O’Donoghue, D. J. (1912). The Poets of Ireland: A Biographical and Bibliographical Dictionary of Irish Writers of English Verse. Hodges Figgis & Co.

- Ramsey, J., & Ramsey, D. Q. (2005). The Piper of Cloone: Father Keegan and the early Gaelic revival. Maunsel & Co.

- Rothensteiner, J. E. (1928). History of the Archdiocese of St. Louis: In its Various Stages of Development from A.D. 1673 to A.D. 1928. Blackwell Wielandy. May 27, 2025, https://archive.org/details/historyofarchdio02roth/page/202/mode/2up

- Smyth, P. G. (1911). Rhyme with Reason: A Garland of Irish Shamrocks, Many of Them Grown in America. P. G. Smyth.

- Sullivan, T. D. (1911). Irish National Poems by Irish Priests. M. H. Gill & Son.

- The Late Rev. J. Keegan. (1894, March 8). Leitrim Advertiser, p. 3.

- Various. (1886a, January). Donahoe’s Magazine, 15(1).

- Various. (1886b, April). Donahoe’s Magazine, 15(4).

* Work or reference hosted on Leitrim Books.